H

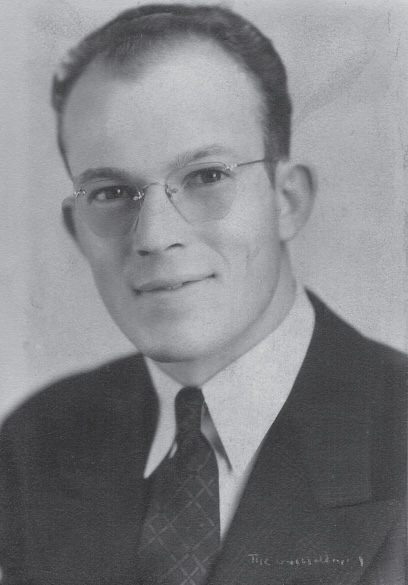

is name was Marvin, and he was 24 years old. He was a radioman on the U.S.S. Arizona, stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. He never made it home to his family in Cañon City.

He was my uncle.

The echoes of Dec. 7, 1941, the “day that will live in infamy,” reverberated for decades in my father’s family and so many others. It was that generation’s Sept. 11, 2001.

As a child, I didn’t understand why my dad left the room when my mom and I talked about Marvin or went through his steamer trunk, which had been stored safely ashore that day.

I didn’t understand why I couldn’t have toys made in Japan.

I didn’t understand why we spent more time with my mom’s family than we did with my dad’s siblings. I eventually realized that it just hurt too much for him to think of who was missing — the older brother he looked up to.

My oldest living cousin was almost 3 years old when Pearl Harbor was bombed, and he vividly remembers seeing our grandfather standing at the family’s mailbox, crying as he read the letter that arrived in mid-December 1941.

For some reason, it wasn’t like you see in movies, with serious-looking military personnel gently breaking the news. Maybe there were too many families to inform at that awful time.

It took me a while to discover that my grandparents didn’t immediately learn that he died that day. I think of the agony they, my dad and his siblings must have been feeling as they waited for the answer.

It affected their friends and neighbors in Cañon City, too. For years, the Daily Record newspaper ran Marvin’s photo and story every December. My mom donated his trunk and possessions to the museum there in 1999, the year after my dad died.

It wasn’t like you see in the movies

My father was barely out of his teens when he joined the Navy and found himself in Honolulu, where they lived from 1948 to 1952. My mom once told me that his grief was still so raw, the tears would stream down his face when he heard “Taps” played to signal “lights out” on the naval base.

It took them decades — until 1996 — to return to Honolulu and visit the Arizona Memorial. They found Marvin’s name on the wall and took photos that I still have.

As my interest in genealogy has increased, I’ve researched Marvin and found documents that chart his journey from Colorado to California and the voyage to Hawaii. The last one is a roster dated late December 1941, listing him as missing in action along with most of his shipmates.

I’ve found photos of Marvin among family collections and on the internet, and I look at them and think about the potential that was lost. I see the twinkle in the eyes of a young man who thought his future was boundless. I wonder what his children would have been like.

One cousin — who also never knew Marvin — and I often talk about our uncle. We’re determined that he will never be forgotten, and that helps us cope with the secondhand grief we’ve lived with as long as we can remember.

I hold no grudge against the Japanese people. Nor do I hate Germans because my mom’s brother was wounded there during World War II. Those tragedies happened because of their leaders’ decisions. And that was then, and we live in the now.

All we can do is learn from those bad decisions, try to find better ways of solving conflict and stop thinking in terms of “us” and “them.”