Eliza Pratt Greatorex (1819-1897), a leading 19th century author/artist/traveler and historic preservationist, is almost unknown today. I became interested in her because she published a slim illustrated volume of her adventures in the Pikes Region in 1872 entitled “Summer Etchings in Colorado.”

I read the book, but didn’t realize at first that she was a much-celebrated artist and author in the mid-nineteenth century, as popular and well-known then as any of her male contemporaries. She was acclaimed as both an artist and a writer during her life but was soon forgotten.

Greatorex’s backstory is that she managed to survive and thrive after her husband died suddenly in Charleston in 1858, leaving her with three kids and little money. She painted, she wrote, she taught and was soon able to support herself and her family.

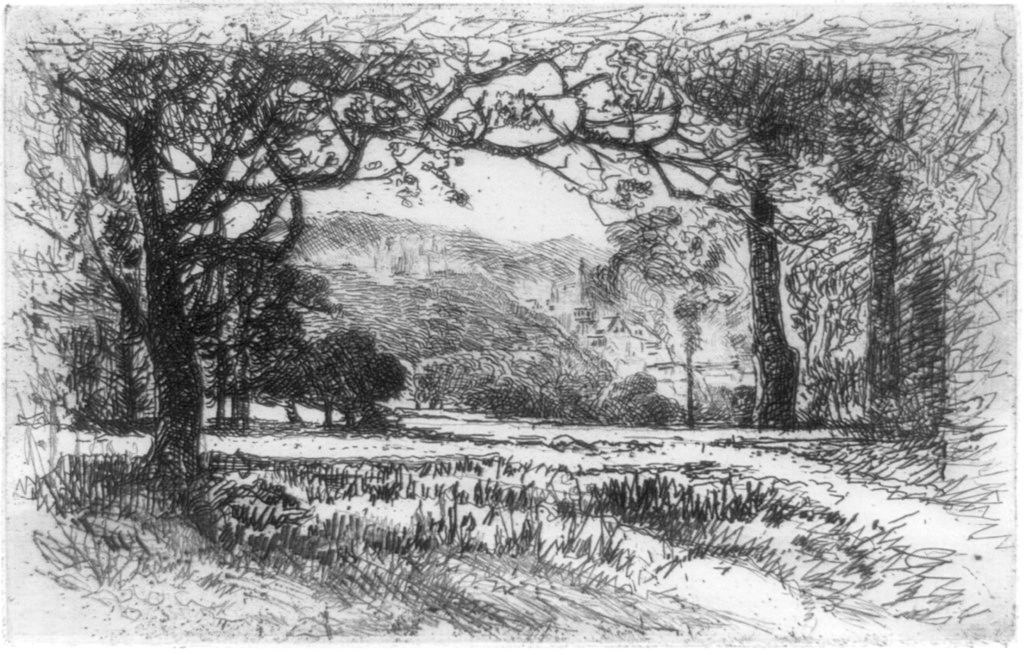

In the summer of 1873, Greatorex and her two grown daughters, Nellie and Nora, came to Colorado and spent several months exploring the region. Greatorex was an acute and sometimes unsparing chronicler of early Colorado Springs and its inhabitants, fascinated by their stories, their heritage and their work. To a modern reader, her prose is Victorian, but her etchings are direct, uncluttered and often masterful. Here’s an account of a hike up the canyon to Seven Falls.

“The fire is made, the kettle boils, the teapot (which has a story of its own, to be told by Nellie someday) is charged with tea. My dear little Abigail opens the big lunch-basket, so exactly suited to the wagon, and which was filled by the generous hands of our Manitou hostess, and we sit down to a delightful meal. The horses are grazing by the camp, and we leave bags and shawls unhesitatingly in the wagon and set out for the falls. I began to count the bridges over that Cheyenne creek, made of stepping-stones and fallen logs, but gave it up when I reached the twentieth; so, we stood before the beautiful falls of Cheyenne Canyon, and tried to realize all their beauty and the foolishness of the attempt to sketch them with a woman’s hand and a steel pen.”

Yet Greatorex didn’t shy away from misery.

“As I approach [Colorado Springs], so peaceful and comfortable-looking last night, children are seated on a chest, one of them crying because father will not let her carry home a pet prairie-dog, which she has on her knee. The old people are packing up bag and basket. A strong young fellow lifting the poor sick wife and mother into the wagon, which must carry them back to their home in Kansas. As the sad little group moves off, I catch a glimpse of a white face pillowed inside; the children sit quietly by the father, who is driving, while the stout old couple walk slowly beside. A sad start for home. She came to Colorado too late; the blessed air cannot heal lungs so far diseased as hers, and, as I turn back sorrowfully to my hotel, I wonder if she will reach her home, or if they will have to stop by the way to seek a resting-place for her.”

An Irish emigrant who came to America in her twenties, Greatorex was ambitious and fiercely talented. Three years after publishing “Summer Etchings,” she went for bigger game, publishing “Old New York: From the Battery to Bloomingdale” in 1875. Dozens of illustrations depicted and mourned then-ruined or demolished buildings in New York City. The book was a collaboration between Greatorex and her sister, Susan Despard, who wrote the text. For the sisters, the city was not just the bustling city of a vast and dynamic country, but also a place of mourning and memory.

Greatorex was also a ferocious feminist before the word was coined, advocating for women in the arts and letters. She fought successfully for female artists to be included in the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876 and never stopped travelling. Both daughters became professional artists, and the three women would often travel together.

A portrait shows Eliza at around age 50, quill in hand and regal in appearance, someone ready to succeed at any endeavor.

But tough as she had to be, she was captivated by beauty. Writing joyfully from a ranch near Colorado Springs, she brings the morning alive.

“Sitting at breakfast the table of rough pine boards adorned with red cloth and a fresh bouquet of exquisite prairie flowers, muttonchops, potatoes mashed and browned to perfection, coffee and milk and cream; near us are cows and horses, and the beautiful, graceful, antelopes; broad slopes of green pasture, with long, cool shadows thrown here and there; skies of purest blue, and mountains – mountains, all around – they surround us, but the grand distances take away the feeling of being imprisoned by them, and Pikes Peak is so softened and mellowed by the atmosphere, that all sharpness and grimness are quite melted away.”

We remember you, Eliza, your words and your art. May we see the beauty before us as clearly as you did.