By William J. Dagendesh

As a boy, the holiday season was reserved for sipping hot chocolate, listening to my parents’ worn 1960s Christmas albums and feasting on mouthwatering, oven-roasted turkey.

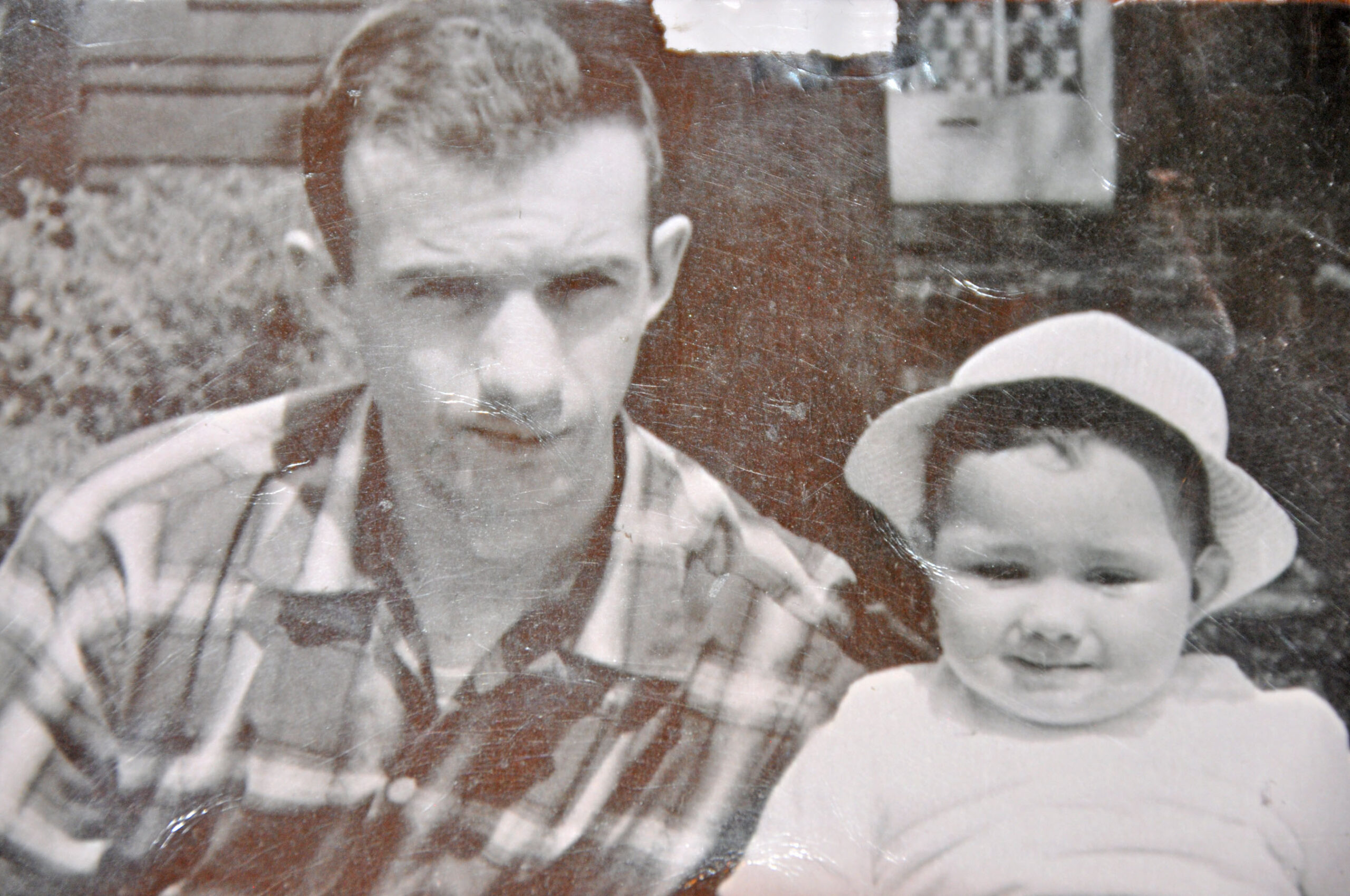

Laughter from my siblings and me filled the air as we ice skated on the Black River yards from our Lacrosse, Wis., home, while Mom basted the Butterball bird to crispy, golden-brown perfection. However, it wasn’t until 1990 that Christmas took on a more profound meaning for Dad and me.

In August that year, the world learned that Iraqi troops had invaded the tiny nation of Kuwait. The invasion resulted in United Nations Security Council members enacting economic sanctions against Iraq and President George H.W. Bush deploying U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia.

In November, I was serving as assistant editor of Flightline, the Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, Texas-based newspaper, when I received orders to U.S. Central Command headquarters in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, as part of Operation Desert Shield. My job was to write about the military’s involvement and assist national media with covering the war. I was scheduled to depart the United States on Thanksgiving Day.

I worried how my parents would take the news. I called home and Dad answered the phone. I mentally searched for the words to say. However, there was no way to sugarcoat this unwelcome news.

“Dad, I have orders to Saudi Arabia. I leave on Thanksgiving Day,” I said softly.

I wanted to retrieve my words as I spoke them. A seemingly eternal silence followed my announcement.

“Please tell me you’re joking,” Dad replied, his voice cracking. “Don’t get hurt, OK?” Dad continued, his voice fading like a sustained note at the end of a song.

After a brief conversation, I said goodbye, hoping I could honor Dad’s request. For Dad, it seemed like a nightmare. His son was going to war and there was nothing he could do to stop it and I couldn’t stop his emotional anguish.

Christmas Day was unlike anything I had experienced. Instead of knee-deep snow, ankle-deep sand covered the ground as far as the eye could see. Instead of 3-hole ski masks, military personnel carried gas masks in case of a biological or chemical attack. Instead of hearing Christmas carols, everyone awaited the sound of Patriot missiles screaming through the night sky.

I attended Christmas Mass and prayed for everyone’s safe return home.

However, on Jan. 17, 1991, Operation Desert Shield became Operation Desert Storm. On that day, Dad fell into an emotional chasm from which his family feared he wouldn’t recover.

An ashen pallor replaced his peaches-and-cream complexion. He didn’t eat and within days had lost so much weight that water could fill the hollow of his collarbones.

I assured Dad I could don my chemical mask in six seconds and could shoot a rifle with deadly precision. However, my comments offered little comfort.

“The Middle East is a cruel, unforgiving environment,” Dad said.

The thought of my returning home in a body bag gnawed at Dad like an incurable disease. Surely, he would have died had a bullet or Scud missile found me.

Mom’s letters explained what was happening at home. Fearing Dad might have a heart attack, Mom pressed him to see the doctor. Instead, he prayed for the war to end and for my safe return home. Even when the war ended on Feb. 28, Dad continued to pray.

“I won’t stop praying until Bill’s feet are back on American soil,” Dad told Mom as tears rolled down his cheeks.

Two weeks later, I was on a military flight home. Residents whistled and cheered as military personnel disembarked the plane at Colorado Springs’ Peterson Air Force Base. Country singer Lee Greenwood’s anthem of patriotism, “God Bless the USA,” poured from 6-foot stereo speakers as well-wishers clutched yellow-rose wreaths and red, white and blue balloons.

Wives’ club members stuck homemade cake, candy and cookie-filled shopping bags in our hands, and Vietnam veterans toasted our return. However, I thought only of Dad who, in my eyes, was the true hero for having endured so much emotional anguish.

My parents’ support was overwhelming. A poster of a bald eagle clenching a “Welcome Home” banner in its talons was taped to the garage door. A blanket-sized U.S. flag hung from the front door, and yellow ribbons tied around the row of pine trees lining the driveway snapped in the warm breeze. A U.S. flag-shaped carrot cake waited for me on the kitchen table and we celebrated a belated Christmas.

The tears in Dad’s eyes spoke volumes. When he found his voice, Dad summed up the nation’s heartfelt appreciation of its uniformed sons and daughters.

“I love you, Bill — Merry Christmas,” he said as he buried his face in my chest and sobbed. I too, cried, thankful for Dad’s love that had nearly cost him his life.

On Aug. 25, 2002, I lost Dad to lung cancer and pneumonia. Even as I held him in my arms, I recalled the anguish he endured 11 years before.

“Thank you for your love and support. Thank you for being my Dad,” I whispered in his ear as he closed his eyes forever.

Although Dad is no longer with us, the memory of that Christmas remains. This year on Christmas Eve, I will light a candle and thank Dad for all he did for his family and, in particular, me.

No son could receive a greater Christmas gift.