Three geese scooted the creek then veered towards a mass of cattails. A coyote slipped into the tamarisk, reappeared upstream, then vanished. Deer prints tracked feeble smears of snow edging the ice. I came to the bridge just after dawn. Along the creek the forest was all faded yellows and shades of gray.

I walked up from Fountain Creek trailing the ghost-whinny of a woodpecker. It moved ahead, elusive, always beyond sight. The sky, a cold, indifferent blue, pushed to the rim of the mountains where gloomy clouds crowded the peaks and ridges. Ponds, frozen in Januarys past, held but thin, spherical lips of ice edging the shore and the base of cat tails. A nuthatch called, a nasally wah-wah-wah. I stopped, but as with the woodpecker, I couldn’t locate the bird.

I remembered a place along Fountain Creek just north of the city of Fountain where a beaver had constructed a dam. I’d stumbled upon it the summer before. The structure grew at the confluence of the Fountain and a brook cascading from the forest. The beaver’s pond was long, skinny, deep, snaking from the dam through an elven copse of elms, willows and sheltering cottonwoods. There, the aquatic rodent had cleared dozens of trees, creating a wide and open meadow filled with water, a rich, wetland ecosystem in the middle of the forest.

We call the Fountain a “creek” because once-upon-a-time it actually was a creek; a thirsty, ephemeral waterway, tributary to the Arkansas River, prone to occasional dramatic floods – but mostly dry. These days, the Fountain runs full and swift the entire year.

The Fountain trickles from snows blanketing the slopes of the 14,115-foot-high mountain most Americans know as Pike’s Peak. The original people of the region, the Tabeguache Ute – Nuuchiu in their own language – know the peak as Tavá Kaa-vi, “Sun Mountain” and the waters birthed from Tavá flow seventy-four and a half miles to its confluence with the Arkansas River at 4,695 feet in my hometown of Pueblo.

Over the years, the Fountain has been dammed, diverted, poisoned, re-routed, mapped, named, channelized, filled with physical and human debris, reduced, augmented, confused, litigated, studied, stolen, replaced, piped, known, unknown, forgotten, remembered, misunderstood, blamed, monitored, sampled, screened, broken and very nearly tamed. More than anything else, humans have altered the very nature of the Fountain, pumping water from Colorado’s western slope into the Fountain’s watershed, making what was once an occasional creek into a full-time river. Given the number of “real” rivers drying up across the American West, the creation of a “new” river is more than a bit mind-bending.

As kids and later in high school we spend a lot of time along the Fountain, exploring, playing, and causing all sorts of trouble. The creek has been imprinted on my mind as long as I can remember.

The Fountain offered me the opportunity to combine my fascination with both history and watersheds. The beleaguered Fountain Creek was itself a story waiting to be told, a story that helps us re-imagine our relationships with rivers and how we might better manage Western waters into the future.

As cement, asphalt, cars, and urban sprawl eats up the Front Range and climate change alters Colorado’s hydrology, I also felt an obligation to bear witness to these changes, to note what the Fountain Creek watershed looks and feels like in the early 2020s.

There is no such thing as inevitability. There is no such thing as fate. The way in which we live today and the way we manage our waters results from choices that were made in the past. And many of those choices were not smart. Thus, we find ourselves in a situation where waterways like Fountain Creek have countless problems and we struggle to manage those challenges.

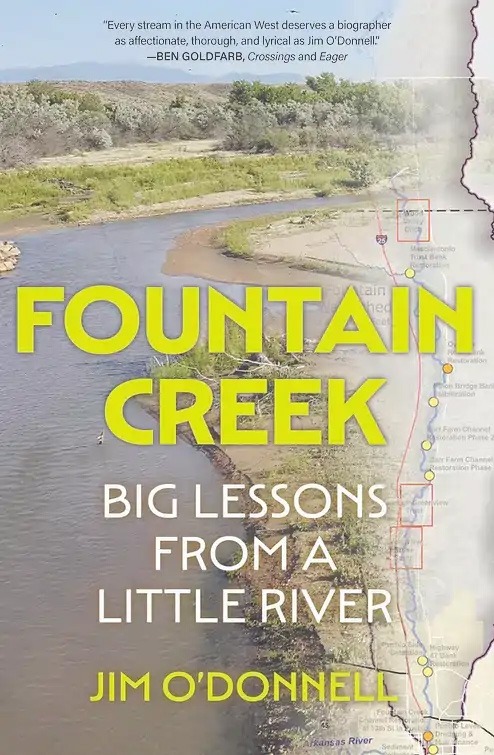

“Fountain Creek: Big Lessons from a Little River” encourages us all to rethink how we approach managing our waters. We create the future through our present-day choices and the future can be whatever we want it to be. It may be purchased at TorreyHouse.org/fountain-creek or in Colorado Springs at Poor Richard’s, Fountain Creek Nature Center, and Mountain Chalet.

This column is brought to Pikes Peak Bulletin readers via a partnership with the Fountain Creek Watershed District.

Jim O’Donnell was born and raised in Pueblo, Colorado. A fifth generation Coloradoan, O’Donnell worked many years as an archaeologist before focusing his eye on public lands protection and watershed restoration. He is the father of three children and writes from Taos, New Mexico with his wife Rasa. He is the author of numerous short works of fiction, countless journalistic articles and the non-fiction work “Notes for the Aurora Society: 1500 miles on Foot Across Finland.” Learn more at: AroundtheWorldinEightyYears.com.

Jim O’Donnell was born and raised in Pueblo, Colorado. A fifth generation Coloradoan, O’Donnell worked many years as an archaeologist before focusing his eye on public lands protection and watershed restoration. He is the father of three children and writes from Taos, New Mexico with his wife Rasa. He is the author of numerous short works of fiction, countless journalistic articles and the non-fiction work “Notes for the Aurora Society: 1500 miles on Foot Across Finland.” Learn more at: AroundtheWorldinEightyYears.com.