Nobody knows exactly when or why Carl (or Karl) Schwanbeck decided to change his name; in about 1870, he took the name Charles Adams, possibly at his fiancé’s request.

If he hadn’t, we could be driving over the Schwanbeck Crossing bridge on our way from Manitou Springs to Old Colorado City.

Schwanbeck was born in Prussia, now Germany; his reported birthdate varies from 1840 to 1845.

Records show that, at age 18, he sailed from Hamburg to New York, arriving in April 1863, perhaps with his family, who may have been fleeing religious persecution or political oppression.

Schwanbeck’s early history is cloudy and the scribbles on old faded records are hard to read. Even worse, his accomplishments as Charles Adams are now mostly forgotten. And that’s something that Betty Armstrong wants to change.

Armstrong moved here from California so her children could be closer to family and attend Manitou schools. She’s been in her current home for about 21 years, and that’s around the time she noticed an interesting headstone in Crystal Valley Cemetery.

She vividly remembers “seeing this beautiful monument to this man and thinking he didn’t have any relatives around him or anything. And what was he doing here?”

An excerpt of the epitaph:

“Charles Adams … Killed in the Gumry Hotel disaster Denver Colo. 1895.”

But before then, Schwanbeck/Adams accomplished a lot for his adopted country, as shown in the newspaper clippings and copies of historic photos that Armstrong has collected.

His resumé included:

1863 — served in the Massachusetts Infantry during the Civil War (one report says he was shot in the lungs during the battle of Gettysburg);

1870 — appointed brigadier general of the Colorado Militia;

1872-1874 —acted as U.S. agent to the Ute Tribe, mainly the White River and Uncompahgre bands;

1874 — co-founded the town of Monument;

1874 — took custody of Alferd/Alfred Packer and heard the notorious cannibal’s first confession;

1874 — worked as a post office inspector;

1879 — negotiated the release of three women and two children taken captive after the White River Ute Agency Battle, popularly known as the Meeker Massacre;

1880-82 — served as ambassador to Bolivia during the Rutherford B. Hayes and Chester Arthur administrations;

1882-1885 — resumed work as a post office inspector;

Mid-1880s — joined the boards of directors of the Colorado City Glass Works and the Manitou mineral water company.

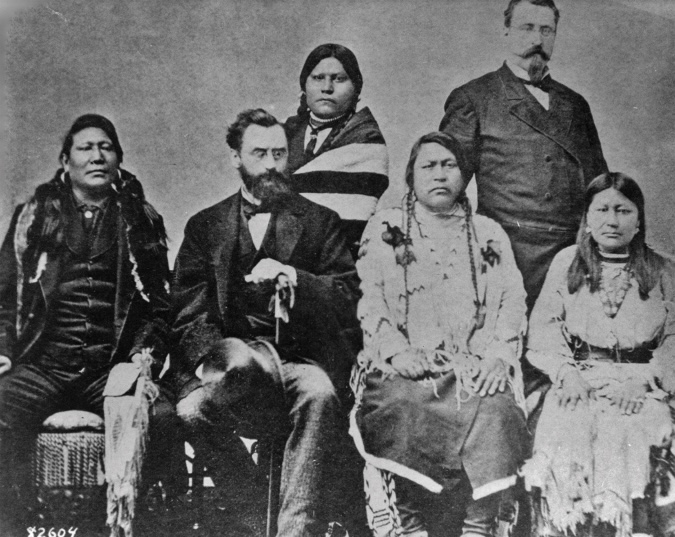

Most importantly for this area, Adams also lived in Manitou, near the spot that Columbia Road meets West Colorado Avenue — today’s Adams Crossing. He and his wife, Margaret, often hosted Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta (namesake of Chipita Park) in their home.

“He was one of the good Indian agents out near Montrose,” Armstrong said.

Adams’ friendship with Ouray is why he was able to secure the release of the Utes’ captives.

The simmering animosity between U.S. agent Nathan Meeker and the Utes boiled over on Sept. 29, 1879. Eleven people, including Meeker, were killed and the Utes took three women and two children as captives.

Speaking of Meeker, Armstrong said, “He was not beloved. Either they became farmers and Christians or get rid of them.”

Adams’ early life history is challenging to state with any certainty, but his death is not.

On Aug. 19, 1895, he was staying at the Gumry Hotel, 1725-33 Lawrence St. in Denver. A basement boiler exploded, leveling the building and killing more than 20 people, including Adams.

Who knows what more he would have accomplished?

Armstrong isn’t sure what she’ll do with all the information she’s compiling. She might write a brief book that gives an overview of Adams’ incredible life, just so people know more about the man who gave his name to the bridge.

“I found that so many people who have been so important to an area, just get lost, get forgotten,” Armstrong said.

Her scrapbook includes a photocopy of the Manitou Springs Journal newspaper of Aug. 24, 1895. It reported that Adams’ body was not recovered from the hotel’s ruins until a few days after the explosion.

“When found, the general was lying on his back with his arms folded across his breast, covered with the mattress of the bed in which he took his last, long sleep. …

“In the death of General Adams, the state loses one of its most prominent citizens — one whose name is indelibly connected with the history of Colorado. …

“He was every inch a hero and his death brings sorrow to thousands in Colorado and elsewhere throughout the country. A brave, loyal, manly heart has been stilled. A good man has gone. Peace to his soul.”