Photography has enlightened, amused and amazed Colorado residents since the 1870s, when pioneer photographer William Henry Jackson loaded his mules with the cumbersome gear of the era and brought back black and white images of the peaks, plains, canyons and historic places of our magnificent state.

Jackson, who was the first to photograph Mesa Verde, Mount of the Holy Cross and many other Colorado landmarks, first came to the territory in 1873 as a member of the Hayden survey. When he subsequently roamed the mountains alone, his two mules carried 300 pounds of equipment.

Wet-plate photography was an awkward and complicated process. Early cameras that could take high-resolution images needed long exposure times — and mountains don’t move.

After exposing his plate, Jackson had to take it immediately into his portable darkroom, a canvas tent lined with pink calico, which prevented exterior sunlight from ruining the image. It took multiple steps, and any error would irreparably damage the plate.

For years, inventors and business leaders sought to perfect dry-plate photography and radically simplify the photographic process.

Rochester, New York, entrepreneur George Eastman was one of the first to market the new technology. He began commercial production of dry plates in 1880, and the world changed. As camera technology evolved, photography democratized. With the advent of the Kodak Brownie 1900, anyone could buy one, take a few snapshots and get them developed and printed.

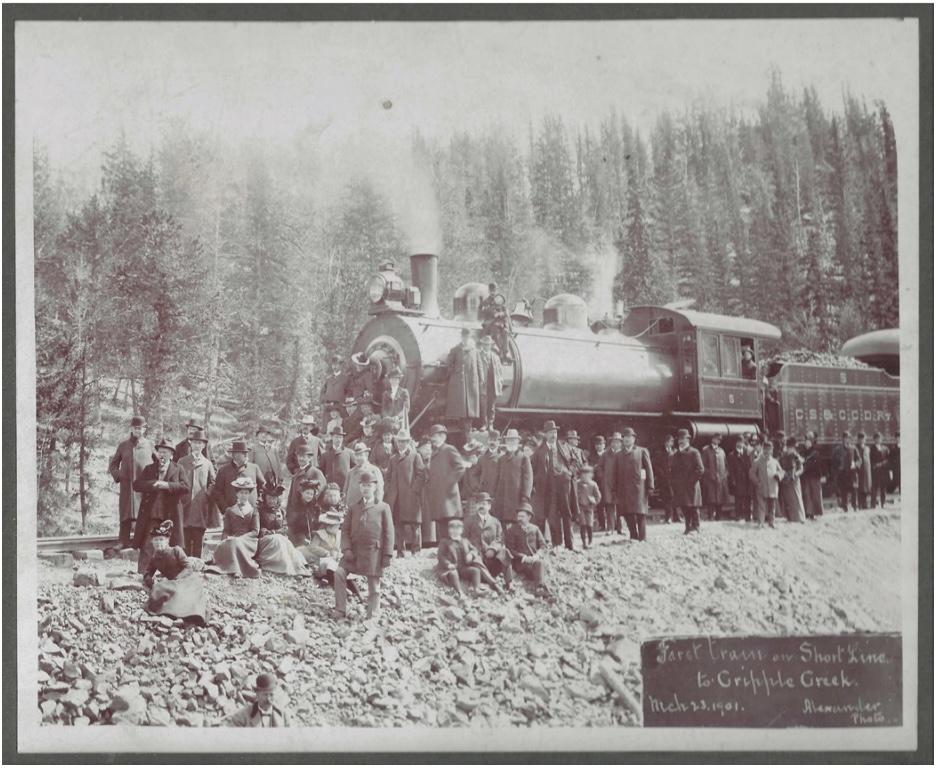

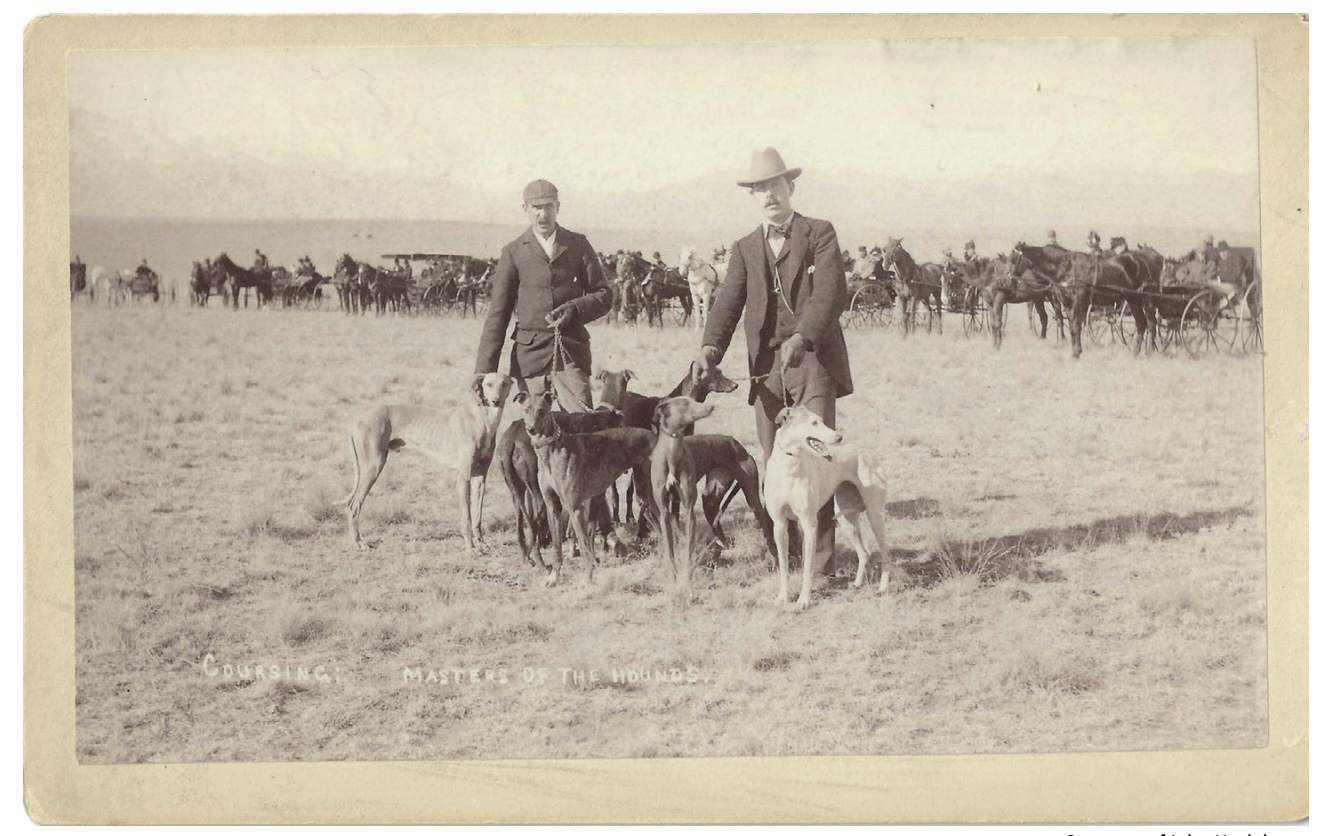

In looking at images created in and around Colorado Springs from the 1880s to the early 20th century, we see both the refined product of the professional and the artless and often wonderful visions of amateurs.

Fair warning: I’m an ardent collector/hoarder/lover of early photographs (as is Bulletin editor Rhonda Van Pelt). Many of the images that accompany this story come from family archives and albums from the 19th century.

Invented by Louis Daguerre in 1839, photography celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1889. The daguerreotype was a technical and scientific miracle, but difficult and awful in practice.

“Can you picture the comic situation of a victim of the daguerreotypist of 1839,” J. Wells Champney wrote in 1889, “screwed to the back of the chair, his face dusted over with a fine white powder, his eyes tightly closed, obliged to sit a full half-hour in the sunlight?”

Wet plate was a drastic improvement, but professional photographers yearned for a process that was faster, simpler and less time-consuming. Dry plate brought that, and a lot more.

By the early 1880s, fashionable Colorado Springs photo studios could quickly make images that are still strikingly beautiful 130 years after they were created. Many survive, preserved in photo albums of “cabinet cards,” spirited photographs of individuals, couples, families and even the family dog.

Consider cards created by Colorado Springs professionals Charles Emery and Horace Poley.

In July of 1895, Poley photographed two handsome dogs, Dick and Chancellor. They had apparently been bathed and groomed for their moment of immortality, and rest quietly and alertly on a light-colored surface. Having laid undisturbed in an album for nearly 130 years, the photos are pristine and (for dog lovers) moving.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1864, Poley moved to Colorado Springs in 1887 and resided here until his death in 1949. He concentrated on photographing Native Americans in the Southwest.

The Pikes Peak Library District owns hundreds of his works, including images of the Fiesta of San Geronimo at Taos, the Snake Dance of the Hopi, Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico and the Dedication of the Ute Pass Indian Trail in 1912.

Charles Emery, who also worked in Colorado Springs, launched his career at age 20, opening his first studio in Silver Cliff, in the Wet Mountain Valley about 90 minutes southwest of Colorado Springs.

“Soon after Emery’s arrival,” wrote photographer-historian and Library of Congress curator Carol Johnson, “smoke from a forest fire in a nearby gulch looked like snow on top of the mountains. The scene so captivated the city’s population that they closed stores and offices in order to view the sight. Emery made stereoviews of the mountain scene, which he later sold by the hundreds for fifty cents apiece. This brought his work to national attention.”

In 1892, Emery bought a studio in the Springs, and worked there for almost 40 years. He specialized in portraits, and would come to your home if you so desired. A photograph of his studio, a one-story building at Cascade Avenue and Kiowa Street, shows a light-filled space with painted backdrops, posing chairs both simple and regal and a gigantic camera on a moveable stand.

Emery had a long and varied career, and was recognized as one of the country’s premier photographers. After the drowning death of his spouse in 1930, Emery committed suicide in 1932. They are buried together in Evergreen Cemetery.

Any error would irreparably damage the plate

And to end on a more cheerful note, let’s consider a favorite: an uncredited cabinet card dated 1889 of a girl whistling on a Nantucket street. On the reverse, someone wrote: “Whistling girls and crowing hens/will always come to some bad ends.”

Her face is familiar — no surprise, since I knew her well. She’s my grandmother, Edith Winslow, then 18 years old. You, and your unidentified friend who wrote the witty little ditty making fun of you, live in memory … and now I need to identify the rest of the photos.

A pleasant task indeed!