The Pikes Peak Bulletin highlights local businesses that support community journalism by advertising with us. For a small, local nonprofit newspaper, advertising revenue is critical, along with reader subscriptions and grant funds.

However, this relationship will never hinder or influence our reporting at any time. If you value local news, subscribe to the Bulletin today and consider us as your go-to platform to get the word out to area residents and visitors.

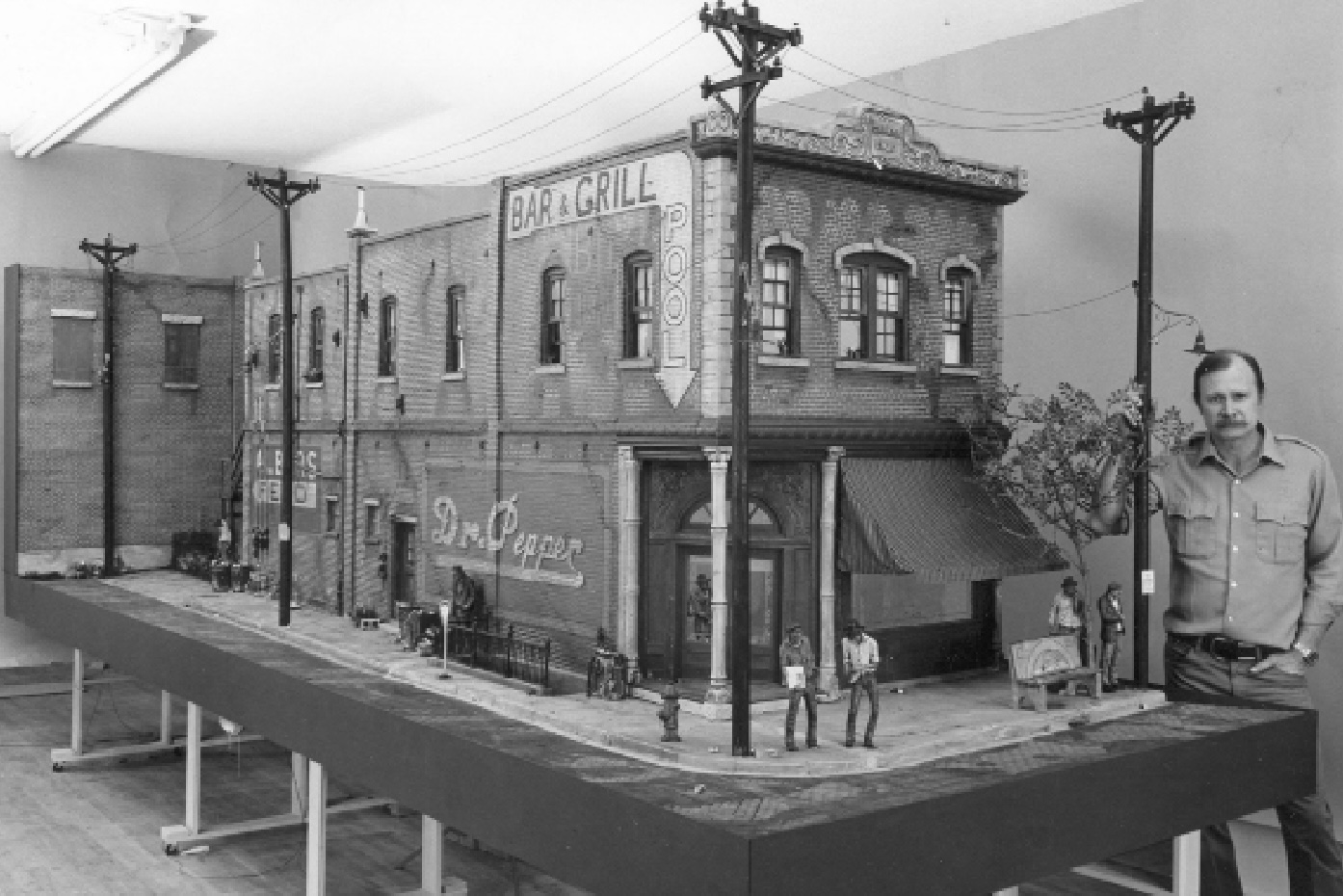

Michael Garman’s Magic Town distills an era in city scenes

It is fitting that the Michael Garman Museum & Gallery is housed in Old Colorado City, and not just because its founder and namesake called this area home. The historic buildings hearken back to another time, connecting us to the past as we enjoy the unique boutiques, restaurants, and other businesses inhabiting those spaces today.

Inside a brick building on West Colorado Avenue, the Michael Garman Museum & Gallery immerses visitors in another bygone era, a certain type of working-class city life that occurred in the 20th century, with painstakingly detailed tableaus at 1-to-6 scale depicting everyday people and scenes, the largest and grandest of which is the 3,000 square-foot miniature city known as Magic Town.

The people are varied and unique, posed in a way that makes them seem paused in an unguarded moment, just living life: a father and son in their living room, a man reading a newspaper on a city bench, a woman talking with the guy running a fruit stand, a young lady standing with her hand on her hip as she contemplates what song to put on the jukebox.

Some are working – a man in a hard hat climbing out of a manhole – while others are relaxing on front steps or in a pub or restaurant, or waiting in line for the cinema. A group of friends plays a game of pool; two men behind some buildings warm their hands on a fire lit inside a barrel.

There are so many details to notice.

What makes Magic Town and the smaller street scenes perfect are the imperfections: the trash can that’s a little too full, the shoe left on its side by the living room chair, the leaves and stray scraps collected in the gutter.

Trick-lighting effects periodically transform certain rooms and alleyways into entirely different scenes, and holograms appear among the sculpted characters and speak. In a diner, a holographic man behind the counter casually relates the story of how he came to own the restaurant as he keeps an eye on the door for incoming patrons.

There are so many details to notice in the scenes that several scavenger hunts have been created, encouraging patrons to have fun looking for certain items.

According to informational materials available at the gallery, Michael Garman created these tiny scenes over the course of nearly half a century, starting in the 1970s.

“These figures are not portraits but are composite sketches of bits and pieces of humanity that Michael … encountered along his travels,” one flier states.

Although the city is not a specific city, and the scenes do not take place in any exact historical moment, the miniature worlds do seem to inhabit some part of the 20th century, or maybe a dream about the 20th century.

The women are mostly in skirts and dresses, the men in long pants. The clothing is mostly without branding or styles to pin it precisely to a certain decade. There are lots of newspapers but no cell phones.

Born in in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1938, Garman showed creative abilities from a young age, making his own toys and crafting figures from pipe cleaners and building detailed scenes for them – an early version of what would become his life’s work.

As a young man, Garman traveled to Los Angeles where he briefly apprenticed in photography. A two-week photojournalism trip in Mexico turned into two years of adventuring through Central and South America, including talking his way into a free stint at a fine arts school. Garman lived among the locals and portrayed their lives in sculpture and film.

“As I hitchhiked across the Americas, the most beautiful things I saw were alleyways,” Garman said, “with the sun reflecting off the bricks, with garbage cans and vines, cats and even rats. It fascinated me. It’s an ugly-beautiful.”

The sublime quality Garman saw in these cityscapes and the inhabitants is front and center in his works; it is, in a sense, the true subject of his art.

Some prominent people, including former U.S. Presidents George Bush and Ronald Reagan, have collected Garman’s work. But Garman felt it was important for everyday people -the types of people he portrayed in his work – to be able to afford his sculptures.

To that end, he created an affordable reproduction technique so he could sell handmade art at affordable prices. Sculptures are available for sale at the museum and gallery, and on the website.

Garman’s son, Michael Patrick Garman, is also a sculptor, and general manager of the museum and gallery, as well as the Broadmoor Fire Department fire chief. He leads a team of artisans to maintain his father’s works and keep Magic Town an “always changing venue” by adding “little dramatic moments of sculptural interaction,” including holiday themes.

The younger Garman said the scenes are made from a mixture of materials. Most of the figures for purchase in the gallery are cast from Hydrocal, a gypsum-based casting material. Some of the more complex pieces are cast in bonded stone (resin filled with marble) for strength and durability.

The brick facades and streets of Magic Town are primarily cast in polyurethane foam with a wood-framed support structure, and the numerous props are made of different resins.

“Other items are designed with ‘anything would work’ – my dad’s words,” he said.

Michael Patrick Garman also said that it was important to him and other relatives to share his father’s works with the world.

“We’re making all efforts to try and continue his legacy, especially through the museum and Magic Town,” he said. “The whole family is interested in Magic Town being able to be seen, just like my father would have wanted, for as long as possible.”