Are you puzzled about the origin of Colorado Springs street names? As a native, I learned that east-west streets were named after mountains, while north-south streets honored rivers. That seemed OK, if a little eccentric, so I figured that I knew enough. The names were the names, so let’s move on.

Irving Howbert’s account of the naming process is interesting, because he was part of the process, not a historian. Born in 1846 in Indiana, he came to Colorado with his parents in the great migration of the 59ers.

The family settled on a ranch on Cheyenne Creek, and young Irving became deeply involved in politics, government and business. He was El Paso County Clerk from 1869 to 1879, and single-handedly created the deal that secured land for the new city of Colorado Springs.

He was young, ambitious and competent.

Marshall Sprague’s “Newport in the Rockies” book describes the street-naming process as chaotic and random. City founder William Jackson Palmer gave his trusted associate, Gen. James Cameron (after whom Cameron’s Cone is named), some guidelines and Cameron sat down and filled in the blanks.

Cameron also delivered the address on July 31, 1871, as the first stake was driven to lay out the city. Inspired (according to Sprague) by “a jigger or two of whiskey,” the general’s speech appears to have been both confusing and uplifting. Having spent a couple of years helping to found Greeley, he apparently referred to Monument Creek as the “noble Cache la Poudre.”

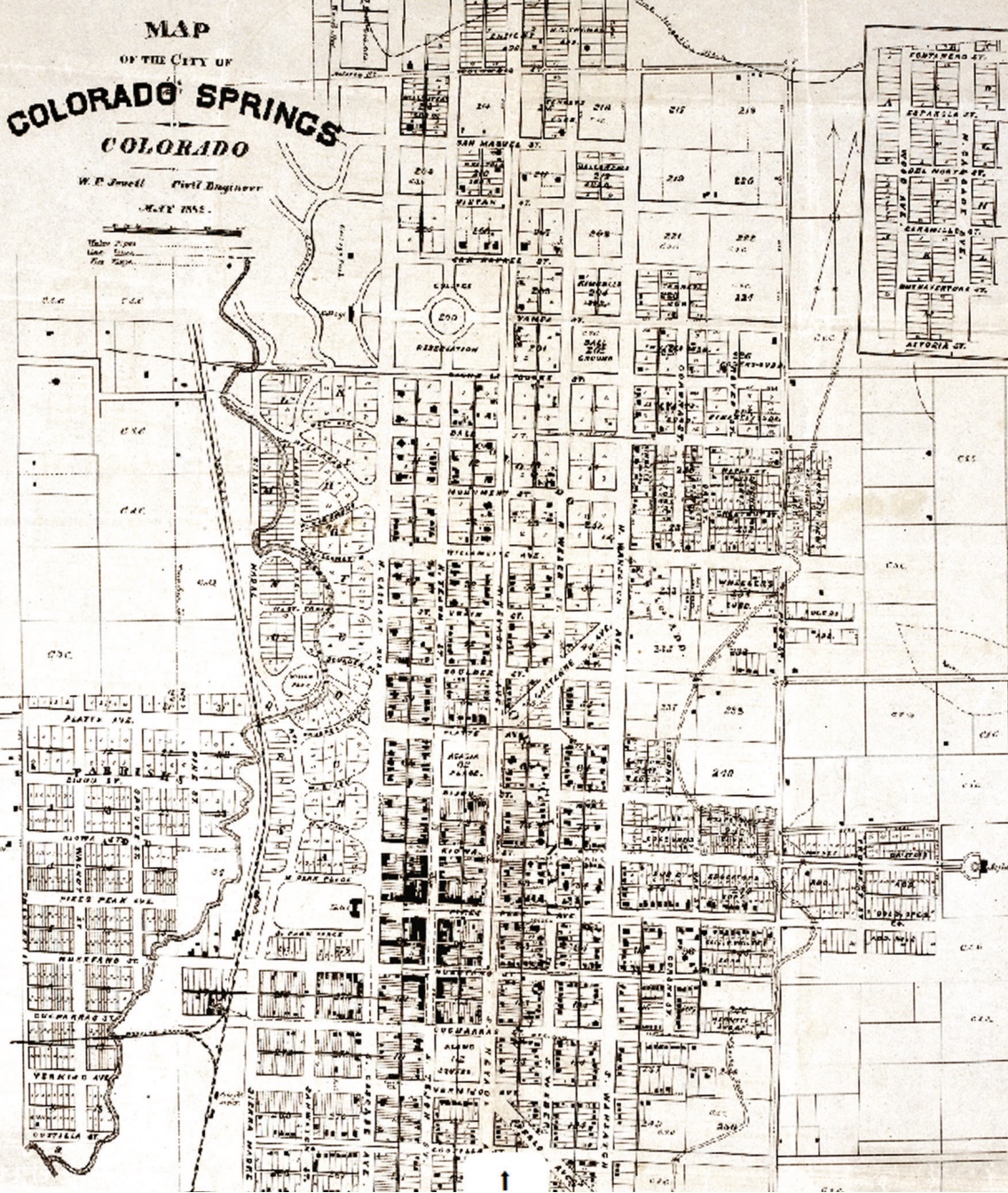

Writing in 1923, Howbert recalled that the names were deliberately chosen to celebrate the “Spanish influence” south of Pikes Peak Avenue and the “French trapper element” to the north. Hence Huerfano, Cucharras, Vermijo and Moreno to the south and Platte, St. Vrain, Bijou and Cache la Poudre to the north.

North/south streets were named after mountain ranges, and the two small parks in the heart of town were given the distinctive names of “Acacia” and “Alamo,” not simply “North” and “South.”

Sprague’s analysis is more detailed than Howbert’s — not surprisingly, since Sprague had been a journalist before coming to Colorado Springs for his health in 1941. For the five previous years, he’d been a feature writer for the New York Times.

He was young, ambitious and competent.

As Henry Ford once said, “History is bunk,” suggesting that we simply choose up sides and believe what suits us. And here’s an example that may resonate with today’s politics and polemics:

In the 1860s, many leading county citizens wanted to build a decent wagon road up Ute Pass.

“Finally,” Howbert wrote, “the question of issuing $15,000 in county bonds to build the road was submitted to the people at an election held on the 20th of June, 1871. Many of the old settlers thought it most extravagant, and predicted that the county would be bankrupted thereby. Nevertheless, it turned out that the progressive, wide-awake citizens of El Paso County were in the majority.”

Yet although Howbert was there, he wasn’t yet the power broker that he eventually became. He was busy with the county’s minutiae, serving as de facto county treasurer, county assessor and all three county commissioners. Sprague saw him as a master manipulator, noting that the Ute Pass bond issue was approved thanks to Howbert’s “threats and cajolements.”

According to the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, “In 1878, Howbert became part owner of a silver mine in Leadville. He became the president of the First National Bank in Colorado Springs in 1880 and a Colorado State Senator from 1882-1886.

“Besides banking, business and politics, Howbert led railway companies, wrote two books and held many civic positions in Colorado Springs.”

And he was proudly woke!