Unlike our Manitou Springs neighbors, we who live or do business in Old Colorado City or the Westside don’t have agency. If our overlords in Colorado Springs want to meter parking in formerly free OCC lots and help themselves to the cash, too bad for us. If traffic to the mountains clogs residential roads, that’s our problem — not theirs.

But problems are to solve, not complain about. Here’s an inspiring tale about Colorado City’s salvation and revival 120 years ago:

In the late 1890s, Denver and Pueblo interests controlled the Midland and Midland Terminal Railways and sought to funnel traffic and business away from Colorado City and Colorado Springs. Passengers and freight from those destinations were overcharged, forcing many to go by stage and wagon teams.

Bad enough, but worse still, the Florence and Cripple Creek Railway (in cahoots with the Midland) was trying to persuade mine owners to build a reduction mill to treat lower-grade ore in Florence. Mine owners didn’t like the idea, but the railroad companies had the upper hand.

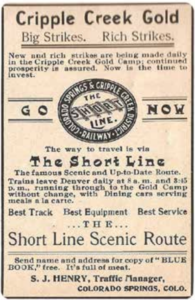

The solution: build a competing railroad. Never mind that a completely new standard-gauge route would have to be constructed through extraordinarily difficult terrain, stations constructed in Cripple Creek and Colorado City, locomotives and rolling stock acquired and shipped, track installed, deals made with mine owners, etc.

Once the problem was identified, the Colorado Springs City Council appropriated money to “ascertain whether or not a direct line to the District was feasible.” Predictably, the politicians couldn’t get anything done.

Irving Howbert led a business group that sidestepped City Council and took full control of the project. They first acquired an electric line that ran between Cripple Creek and Victor. Then, they sent Howbert to Washington, where he “secured the passage of a right of way over the Pikes Peak Forest Reserve.”

That was in March of 1899. By September, surveys were completed, money raised from investors and construction began. They didn’t waste time — both passenger and freight lines were completed and running in 15 months, at a cost of $1.5 million.

WE’RE GAINING a little more clout.

Can you imagine, 120 years later, our sluggish bureaucracies conceiving, planning, building and finishing such a project in 15 years, let alone 15 months?

To the delight of mine owners and local businesses, the Short Line’s competitors launched a rate war. Laden with debt and unable to compete, they were bankrupt in eight months. The Short Line’s time of dominance began.

Cripple Creek ores were treated at a newly built reduction mill in Colorado City, employing hundreds for decades (sorry about that, Florence!) and Colorado Springs/Colorado City residents enjoyed the new scenic line.

But the canny Howbert and his fellow investors knew it wouldn’t last.

“Under the best conditions,” he wrote, “a short line among numerous larger systems is in a difficult position.”

Gold production was declining, so they sold to Colorado and Southern in 1904, giving the shareholders a nice profit. Years later, the line was abandoned and transformed into an auto toll road, which eventually became Gold Camp Road (now, alas, closed to vehicles).

Here in OCC and the historic Westside, we may embody the city’s history, but we sometimes feel like an inconspicuous cog in a big machine. We’ll never have complete autonomy, but we’re gaining a little more clout.

Sallie Clark has a senior position in Mayor Yemi’s administration, while City Councilors Michelle Talarico and David Leinweber have long owned businesses on the Westside. And the mayor himself shows up frequently at local events, even one celebrating the revival of a local weekly newspaper.

We’re just one of many neighborhoods in a sprawling city — but we’re arguably the coolest one. Irving and his buddies prevailed against the odds, and so can we … even without $1.5 million