“We know that for those who love God all things work together for good,” wrote Paul in his epistle to the Romans. Nancy Hawley, the administrator and clerk of the vestry at St. Andrews Episcopal Church, was reminded of the apostle’s words after teens broke into the church last week, following news that the historic Manitou Springs church would be closed and sold.

“There’s always something good that comes out of everything bad,” she said. “In the break-in, when I’m going through all this paperwork and trying to re-sort it again, I ran across this little bitty article. It was like three by two [inches], and in that article, there were two paragraphs. The last paragraph said that there is a cornerstone, how it’s marked – the 1905 and at St. Andrew’s cross, I knew where it was right away – and that there is a time capsule in there.”

On Monday, Hawley, Rev. Matt Holcombe of St. Michael the Archangel Episcopal Church in Colorado Springs, and Andy Detvay, St. Andrew’s sexton, were joined by a small crowd of congregants, members of the Manitou Springs Heritage Museum, and curious passers-by to remove the cornerstone and unearth the 120-year-old time capsule.

“We’re very excited about opening this up,” said Hawley. “I don’t think we’ve had anything in town like this for 50 years. This is exciting. For a lot of folks, there’s a lot of history here. The church itself is 120 years old. The congregation is 150 years old.”

Michael Maio, president of the Manitou Springs Heritage Museum, noted that before the stone church was built in 1905, congregants held services in a wooden A-frame building. When the new church was built, the wooden structure was moved across the street, and now houses Anna’s Apothecary.

“One of the things many people don’t know is although this [cornerstone] says 1905, there were Episcopalians gathering in Manitou Springs starting in 1874,” Holcombe told the crowd. “That’s over 150 years that there have been faithful Episcopalians gathering, and so we’re so grateful for the legacy that we have to honor.”

Removing the cornerstone was a comedy of errors. After the participants had gathered at the church, Detvay learned that the tools he was planning to use for the endeavor had accidentally been donated with other items as volunteers cleaned out the church in preparation for the closure. He was able to borrow another drill, with masonry bits, hammer, and chisel, but the battery-powered drill soon ran out of juice as Detvay worked through nearly 6 inches of 120-year-old masonry.

A member of the crowd, in a faux-fur hat with ears, found a replacement drill, which also gave out after another hour of use. Another drill with a plug and an extension cord ultimately did the job. The Manitou greenstone of the church – taken from the Ute Pass quarry west of town, which opened around 1884 and closed in 1938 – proved difficult to work with. As Detvay and Holcombe took turns working a chisel into the drilled-out cracks between the stones, bits of the stone flaked off, making it difficult for the tools to find purchase in the heavy cornerstone.

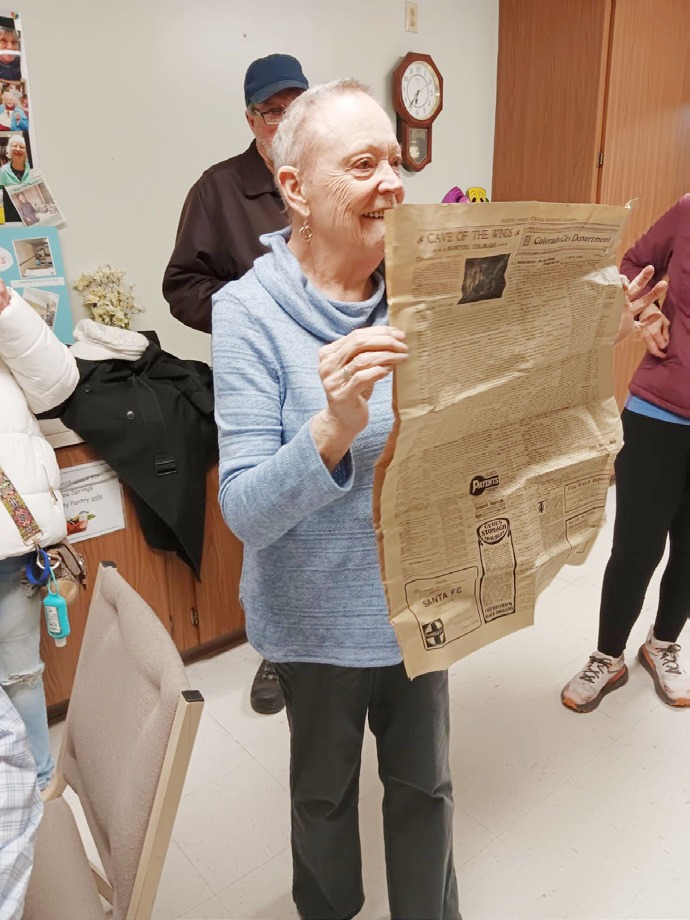

After two hours of work, Detvay, Holcombe, and a party of volunteers removed the stone and revealed a tin box. In St. Andrew’s parish hall, Hawley and Holcombe opened the time capsule.

“A mission was organized by the Reverend Walker,” Holcombe read from a letter in the tin box. “Services were kept up and the cornerstone of the new church was laid June 29th, 1880. An A-frame chapel was built for $1,200 and was ready in March of 1885. The Reverend Hunter was appointed missionary shortly after Mr. Arnold, a former Methodist minister, was made deacon and placed in charge. He built the rectory. The cost was $3,500 on December 1887. Wow. Reverend Hartley was given temporary charge. Reverend Wells was next in order. This was longer than the average. Reverend Hager succeeded and remained until 1896 and then the Reverend Leffler became rector. He resigned September 1898. Reverend Franklin, Colorado Springs kept the service until May of 1889.”

In addition to the letter were church circulars, photos, coins, and a copy of the Manitou Springs Journal from 1905, featuring a story titled, “What is Electricity?” on the front page. The contents of the time capsule will be reviewed by the Episcopal Church’s Diocese of Colorado, and some items may be considered for donation to the Manitou Springs Heritage Museum.

“The diocese needed to review those items inside the box before they donate those to the museum,” said Maio. “They have a deconsecration service scheduled for Thursday [March 6]. The bishop of the Episcopal Church that will be coming down will be reviewing the contents of that box.”

“The stuff is just invaluable”

While the contents of the box are under review, Maio noted the Heritage Museum was granted access to a number of historical records kept by the church. “[Hawley] took us back into her office and she took us into her office and showed us several boxes containing records of the church, which proved to be pretty exciting,” he said. “There were some old logs describing financial transactions, old logs that describe the membership of the church dating all the way back to its founding … membership records, birth records, death records, marriage records, and she offered to copy those records and donate those to our museum. The reason why she could not give us the original is because the Diocese rules require that those records be given back to the Diocese.”

Maio said Hawley also brought out around a half dozen other boxes containing images of the founders of the church – married couple Edward and Ann Nichols – as well as photographs of Manitou Springs founder William Bell, and older images of the church. The Heritage Center was also able to view newspaper articles describing different things affecting the church throughout the years, as well as correspondence.

“I mean, the stuff is just invaluable,” Maio said. “This church actually represents the early history of Manitou Springs since some of our founders of Manitou.”

For Hawley, the time capsule is a bright moment in an otherwise unhappy affair. “Some people were born and raised here,” she said. “We’ve got a couple of people that are like second and third generation Manitoids having some real difficulty accepting this … Everybody can grieve to some degree. I’ve already had some people that came [to the time capsule event] and left because they were crying already. It’s so hard, so hard because they put a lot of love into this place.”