Full disclosure: Gail Binkly is a longtime friend and former professor of Rhonda Van Pelt, the Bulletin’s editor-in-chief.

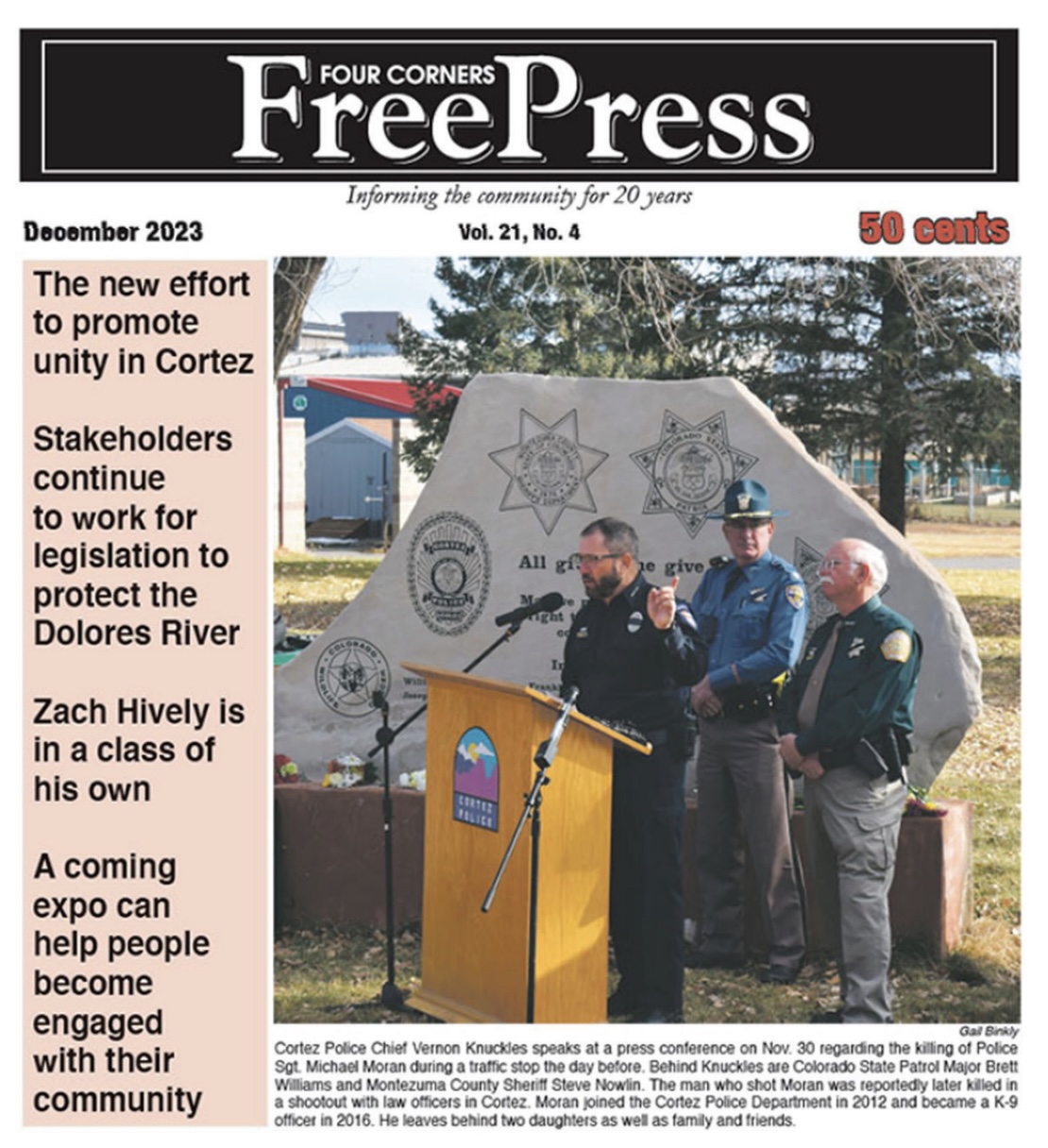

The Four Corners Free Press, an alternative mont hly based in Cortez that served up award-winning news coverage, a wide range of editorial voices and even a popular police blotter, will publish its final edition next weekend, ending a 20-year run and becoming another casualty in the decline of rural print publications.

Co-founder and editor Gail Binkly pointed to rising printing costs — a recurring theme among many struggling rural papers — and the loss of advertisers during the pandemic as factors in the decision to close the paper she owned along with her husband, David Long, and Wendy Mimiaga.

She added that they’ve long been operating on a shoestring, but that the economics finally became untenable.

“It really hasn’t been viable for a long time,” Binkly said. “We just made enough money to scrape by every month. We like doing the paper and we’ve been doing it basically without paying ourselves for a while. But it’s just getting more and more difficult to do.”

After starting her journalism career as a sportswriter in Colorado Springs, Binkly taught mass communications at what’s now known as Colorado State University Pueblo before moving to Cortez. She worked for 11 years at the Cortez Sentinel/Montezuma Valley Journal, including two years at the renamed Cortez Journal.

She and Mimiaga, who shot photos for the Journal, had disagreements with management when the paper changed publishers and decided to pursue their own venture, with Binkly running the news side and Mimiaga handling the advertising.

“We really just thought there should be a regional kind of newspaper,” Binkly said. “We wanted to offer something that was more in-depth.”

She recalled traveling to Salt Lake City to cover the trial of Phil Lyman, a former San Juan County (Utah) commissioner who led a 2014 protest against the Bureau of Land Management, and to New Mexico to cover protests at the controversial proposed Desert Rock power plant on Navajo tribal lands.

The Free Press also featured freelance reporting from the Grand Canyon on bison issues and covered controversy surrounding development at Wolf Creek.

But she credits her husband for writing perhaps the publication’s signature attraction.

decline of legacy newspapers also affects democracy

“The most popular thing in our newspaper honestly, is the police blotter,” she said, “because he tries to write it in a way that makes it interesting, sometimes humorous.”

Binkly, 67, hopes the Four Corners Free Press is remembered as “just something that provided an alternative voice and filled a void and covered some issues that weren’t being covered.”

Mark Stevens, a longtime Colorado journalist and author who moved to the area nearly five years ago, described the Free Press as “quirky in the best way.”

“It had lots of really good journalism,” said Stevens, who has contributed book reviews.

“Usually, every issue features a couple or three stories that are a really good analysis of something going on, covering an issue. And then behind that, just lots of voices — so many different columnists and points of view. And she really wanted the whole spectrum of what’s down here.

“So it just becomes a chorus of the community.”

Although the Free Press had only about 275 paid subscribers, the bulk of its distribution came from news racks and coin-operated boxes — nearly 40 spread throughout the region. Single copies of the paper sell for 50 cents ($12 a year by subscription).

“It has been the price forever and part of the reason — this will probably make you laugh — is because we were given some coin-operated newspaper racks from other papers that had been out of business,” Binkly explained.

“They were set for 50 cents, and we don’t have anybody that knows how to reset them. We’ve had people suggest that we should just get a bunch of new racks and charge more, but it’s difficult to even find racks anymore.”

In retrospect, Binkly figures that naming the publication the Free Press might not have been the best choice. One of her “great irritations,” she said, has been readers who assume from the name that the paper is free and simply grab a copy from the racks at a business without bothering to pay the cashier.

The Cortez Journal will still serve the region’s readers.

The loss of local newspapers, especially in rural areas, has become a nationwide problem as well as an object of concern within the state. Some estimates count 2,500 papers in the U.S., and more than 50 in Colorado, as being lost since 2005.

Many smaller operations have not embraced technology behind online publication and still embrace a stagnant business model built on low-priced newspapers and print advertising.

Last fall, the Colorado Sun outlined many of the challenges facing small and rural papers in its project “Final Edition: Saving Local News” and also noted the recent closing of the Colorado Springs Independent.

The decline of legacy newspapers also affects democracy, as it creates information gaps that make it more difficult for voters to make informed choices, while powerful institutions lack oversight by watchdog reporters.

“In the past few months, ironically, we’ve had people calling us up,” Binkly said.

“They’re saying we need to write about this and we need to write about that, or somebody needs to investigate this local government entity and so on. And we don’t have the resources to do that. There are gaps that aren’t being filled and it’s unfortunate.”

Although the Four Corners Free Press does have a website, Binkly notes that it’s not much of an online presence and basically amounts to “a really good archive.” She and her co-owners have thought about conversion to online-only, but the logistics — and the economics of online advertising, which is less lucrative than print — seem daunting.

And so Binkly will send the final edition, which explains the publication’s farewell, off to the printer in Santa Fe and then fill the racks for the last time. Some locals are already saddened by the loss of a local institution.

“You hate to lose local journalism at any level,” said local resident Chuck Greaves, author and former contributor to the publication’s book reviews.

“Gail really had her finger on the pulse of the community. And it’s a voice we’ll certainly miss down here. Even though the readership may not have been large enough to keep it afloat, I think it was a passionate and dedicated readership.”

The Colorado Sun is a nonprofit reader-supported news outlet. To learn more and subscribe to free newsletters, go to coloradosun.com.